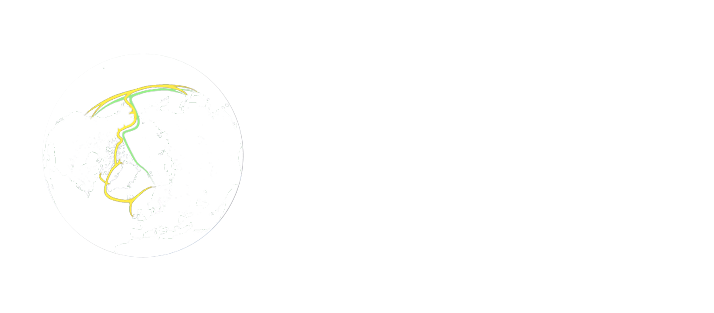

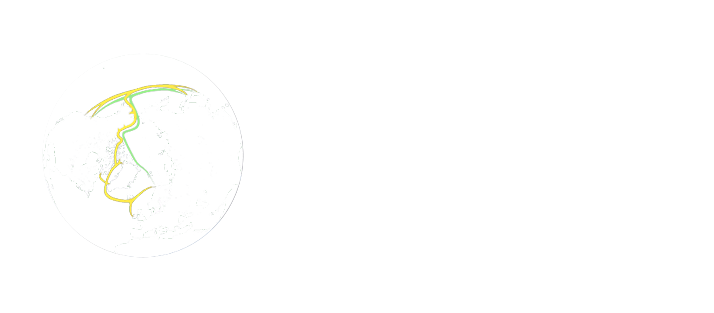

The planned subsea cable Polar Connect will cross the floor of the Arctic Ocean which is one of the least mapped parts of our planet. A route close to the North Pole seems most favourable from a geological viewpoint.

A route almost touching the North Pole will be the shortest and one of the routes with fewer geological hazards for the upcoming Polar Connect cable from Northern Europe to Asia and North America. This conclusion transpires from a study by the Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, as part of the Northern EU Gateways project.

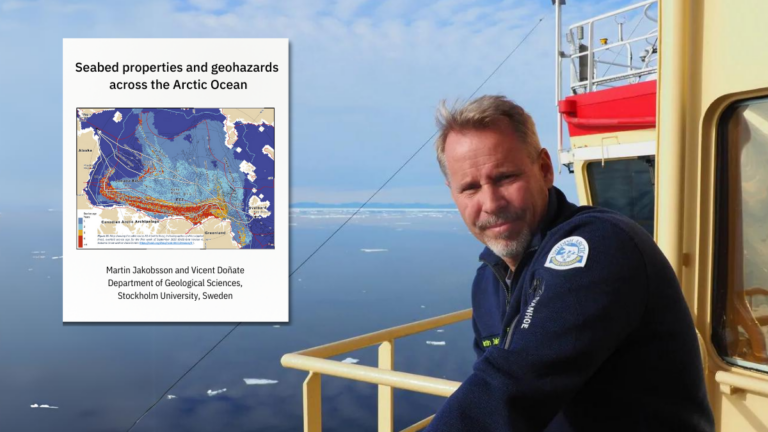

“Since this is a desktop study, our results are only preliminary. To recommend a specific route, we will need to do a detailed on-site mapping of the bathymetry (the seabed topography, ed.) and seabed geological composition,” says Professor Martin Jakobsson of the Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, lead author on the study.

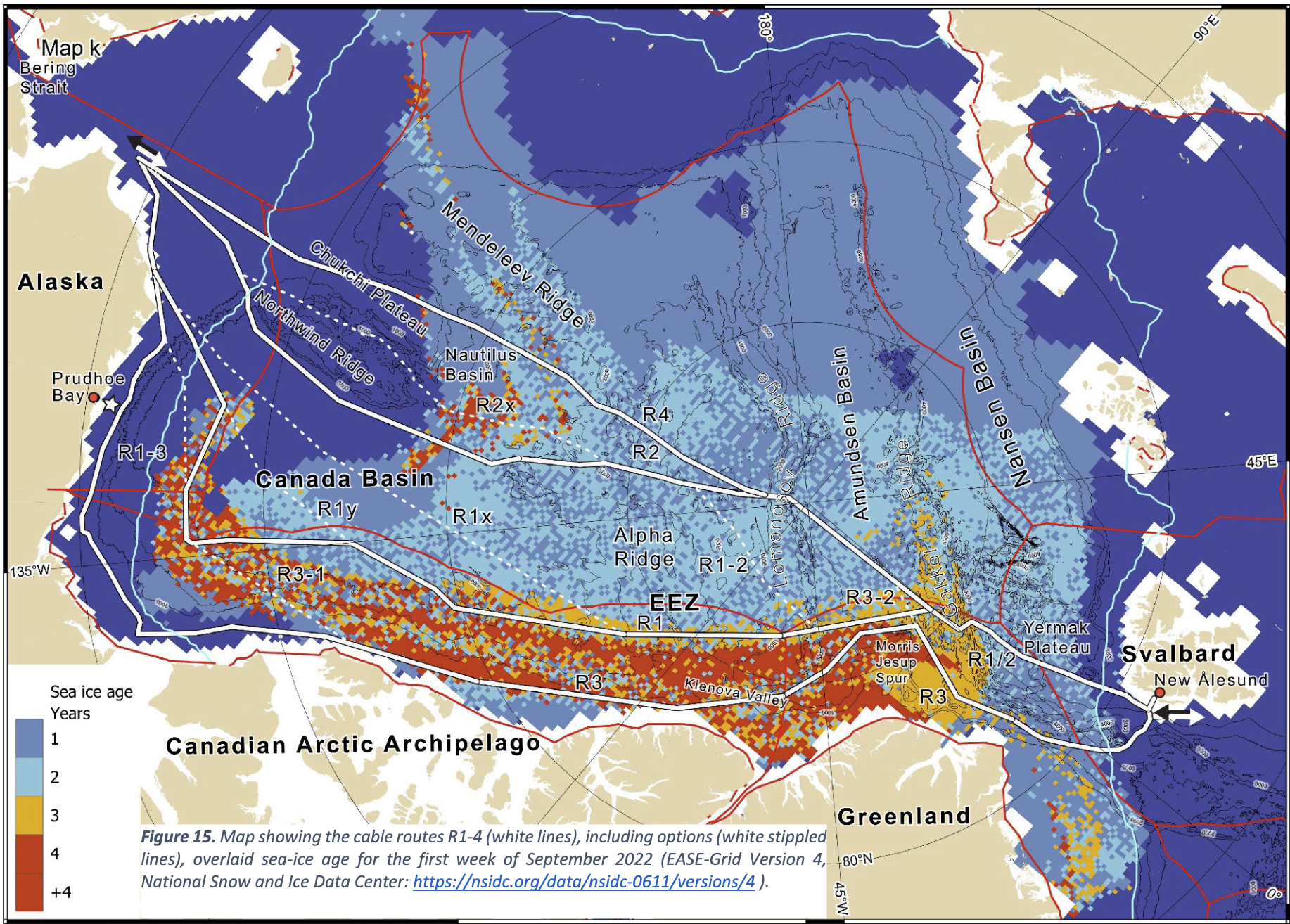

For four possible alternative routes, the study pinpoints a range of challenges relating to both fundamental geology such as steep underwater mountains or slopes, and to dynamic factors such as ice conditions.

“Overall, we can say that laying a cable across the Arctic Ocean is perfectly doable. Several geohazards will be at play no matter which of the routes you look at, but that would be the case for any ocean,” says Martin Jakobsson.

Wise to avoid shallow waters

Broadly speaking, the geohazards of the Arctic Ocean are of the same magnitude as for other seas. What does add to the logistical complexity, however, is the sea ice cover.

A challenge here is ice scouring in shallow waters. If an iceberg gets stuck at the bottom at a location with a subsea cable, the forces at play may soon break the cable. This can happen in some areas rather frequently at all depths smaller than 60 meters, with 30-40 meters as the most critical interval. Therefore, the choice of route should minimize the sections in shallow waters. For this reason, a route close to the North Pole and avoiding the shallow shelves seems to be best.

“I should underline, that we have only considered the potential challenges from a geological perspective. Since we do not have expertise in cable-laying, experts from that field must be involved in a subsequent phase. Further, we have not undertaken any legislative or geopolitical considerations. Some of the routes stay within the Exclusive Economic Zones of certain states, while others are partly in international waters. This may have consequences, but these are outside our field of expertise and not part of the assignment given to us,” says Martin Jakobsson.

A case of fortunate timing

The study has been able to draw data from two international mapping projects, the International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean (IBCAO) and the Nippon Foundation GEBCO Seabed 2030 project. Seabed 2030 supports IBCAO with the goal of having the Arctic Ocean seafloor mapped by 2030. About 25 per cent of the Arctic is mapped by now.

There is also a project linked to IBCAO with the goal of mapping the uppermost sediment geology, which has been beneficial for the desktop study, Martin Jakobsson notes:

“This is yet another example of how fundamental science often proves valuable in ways that were not originally foreseen. When the international collaboration was initiated more than a decade ago, nobody thought of a subsea cable across the Arctic Ocean as a viable possibility. The motivation was purely scientific, but the timing just happened to be fortunate. Without data from IBCAO and Seabed 2030, it would hardly have been possible to compile a meaningful desktop study.”

Still, it must be remembered that the quality of the underlying data is far from uniform for the various parts of the Arctic Ocean.

“We have some parts that are mapped extensively in good detail such as the Fram Strait (the waters between Greenland and Svalbard, ed.), while the opposite is true for other parts such as the Alpha Ridge (an underwater ridge close to the North Pole, ed.).”

Profiling must be done the hard way

In the absence of data from extensive, systematic campaigns, the assessments for several parts of the central Arctic Ocean region are often based on less accurate acoustic measurements by submarines.

“Submarine measurements are helpful, but not satisfactory for an assessment of geo-hazards. Firstly, we cannot get the raw data and can therefore not verify the findings. And secondly, these are single-beam measurements which give a very crude picture,” Martin Jakobsson comments.

“To map the bathymetry in the level of detail required for planning a route for a subsea cable, you must do an on-site campaign involving multi-beam measurements and sub-bottom profiling. This can only be done the hard way, meaning from the sea surface with the help of very powerful icebreakers.”

A fantastic scientific opportunity

Media reporting on the effects of global warming may lead some to think that the Arctic Ocean doesn’t have much ice cover anymore, but that is far from correct, the Professor notes:

“When I plot the experience from all the expeditions, I have taken part in since my first in 1996, I can testify to a significant reduction in sea ice over the entire period. Still, this is of little consequence for the part of the Arctic Ocean we are considering in relation to Polar Connect. These waters remain packed with ice all year round.”

Only the heaviest icebreakers can operate here, and a cable-laying campaign will have to happen in August and September during the annual sea ice minimum. The same goes for science campaigns.

“Producing the geo-data needed to find the optimal route for Polar Connect will be a huge task, but as a scientist I also see this as a fantastic opportunity. A lot of new science will come out of this, and at the same time we know the results will be applied for a project of large societal importance.”

The report “Desktop study: Seabed properties and geohazards across the Arctic Ocean” can be found here

A cable across the Arctic Ocean

The study considers four alternative routes (R 1-4) for Polar Connect. The white stippled lines are possible modifications. The sea ice cover is derived from data for the first week of September 2022.